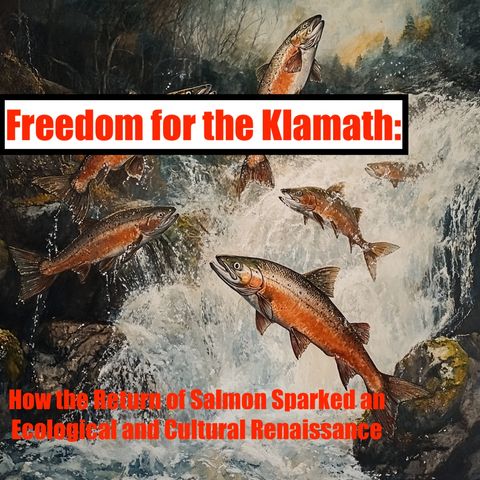

Less than a month after the removal of the Klamath River dams, members of the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes gathered along the riverbanks to witness a moment they had dreamed of for decades. Salmon, long denied access to their ancestral spawning grounds, were returning, leaping through newly opened waterways on their journey upstream. For these tribes, the salmon’s return is more than a natural phenomenon—it is a profound cultural and spiritual milestone. The sight of these fish reclaiming their waters symbolizes resilience, justice, and the unbreakable connection between people and the natural world. The Klamath River has always been a lifeline for the Indigenous peoples of the region, sustaining their diets, traditions, and spiritual practices. For centuries, the river and its salmon runs represented abundance and renewal, woven into the fabric of tribal identity. When the dams were constructed in the early 20th century, blocking salmon migration and degrading the river’s health, the tribes experienced not only environmental devastation but also cultural and spiritual loss. Over the decades, tribal leaders emerged as powerful advocates for the river’s restoration, fighting tirelessly to remove the barriers that had disrupted their way of life. The removal of the Klamath River dams in 2024 marks a turning point, not only for the river’s ecosystem but also for the Indigenous communities that have championed its restoration. It is a story of environmental justice and cultural revival, demonstrating the power of perseverance and the importance of centering Indigenous leadership in conservation efforts. The salmon’s return is a testament to what can be achieved when people work together to heal the wounds of the past and restore balance to the natural world. Part 2: The Klamath River and Its Cultural Significance to Indigenous Tribes For the Indigenous peoples of the Klamath Basin, the river is more than a geographical feature—it is a living entity, a source of life and a sacred being deserving of respect and care. The Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes have lived along the Klamath River for thousands of years, building their cultures and communities around its waters. The salmon, in particular, hold a central place in their traditions, symbolizing abundance, resilience, and the interconnectedness of all life. In the Yurok language, the word for salmon, “Pulik,” is often spoken with reverence, reflecting the fish’s role as both a provider and a spiritual guide. Ceremonies marking the start of the salmon run are among the most important events in the tribal calendar, bringing communities together to honor the river and express gratitude for its gifts. Oral traditions passed down through generations tell stories of how salmon taught humans the importance of reciprocity and balance, lessons that remain central to tribal worldviews. The construction of the Klamath River dams disrupted this deep connection, severing salmon migration routes and decimating fish populations. For the tribes, the loss of the salmon was not just an ecological tragedy but a cultural and spiritual crisis. Ceremonies tied to the salmon run became reminders of what had been taken away, and the river, once a symbol of abundance, became a site of struggle and mourning. Despite these challenges, the tribes never abandoned their role as stewards of the Klamath River. Their worldview, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of humans and nature, fueled their determination to protect and restore the river for future generations. Tribal leaders argued that the health of the river was inseparable from the health of their communities, making the fight for dam removal a matter of survival and justice. Part 3: Decades of Tribal Advocacy and Collaboration The path to removing the Klamath River dams was long and fraught with challenges, but it was ultimately made possible by decades of tireless advocacy from Indigenous tribes, supported by environmental organizations, scientists, and policymakers. For the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes, the struggle to restore the river was deeply personal, tied not only to the health of their environment but also to the preservation of their cultural identity. Over time, these efforts coalesced into one of the most significant ecological restoration projects in U.S. history, setting a powerful example of what can be achieved when diverse groups unite around a common goal. The fight to restore the Klamath River began in earnest in the 1980s, as tribal leaders sought to address the devastating impacts of the dams on salmon populations and water quality. At the heart of their advocacy was a simple but powerful message: the river must flow freely for life to thrive. This message resonated with environmental organizations, which joined forces with the tribes to build a case for dam removal grounded in both cultural significance and scientific evidence. One of the early milestones in this journey was the recognition of tribal fishing rights under federal law. For decades, the tribes had fought to reclaim their right to fish along the Klamath River, a practice that had been severely restricted due to declining salmon populations. Legal victories affirmed these rights, strengthening the tribes’ position as stewards of the river and reinforcing their calls for comprehensive restoration efforts. By the late 1990s, the push to remove the Klamath River dams had gained momentum, bolstered by growing public awareness of the environmental harm caused by the structures. Studies showed that the dams were no longer economically viable, generating relatively little electricity while imposing significant ecological costs. This shift in perception opened the door to negotiations between the tribes, government agencies, and the owner of the dams, PacifiCorp, a utility company. The turning point came in 2010 with the signing of the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA), which laid the groundwork for the eventual removal of the dams. The agreement represented a landmark moment in collaborative conservation, bringing together stakeholders with often conflicting interests, including farmers, fishers, environmentalists, and tribal leaders. At its core was a shared recognition that the health of the Klamath River was critical to the well-being of all who depended on it. Despite the progress made, the road to dam removal was far from smooth. Financial and political obstacles threatened to derail the project, and opposition from some local communities created additional challenges. Critics argued that removing the dams would harm agricultural operations reliant on irrigation and raise energy costs for the region. These concerns had to be carefully addressed through outreach and compromise, with tribal leaders often playing a key role in bridging divides. One of the most powerful aspects of the tribes’ advocacy was their ability to frame the issue as not just an environmental concern but a matter of justice. The Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes emphasized the historical injustices inflicted on their communities, from the forced loss of land to the ecological devastation wrought by the dams. They argued that restoring the river was not only about saving salmon but also about healing the wounds of the past and ensuring a sustainable future for generations to come. Throughout this process, the tribes worked closely with scientists and conservationists to strengthen their case for dam removal. Studies conducted over decades provided clear evidence that the Klamath River ecosystem could recover if the dams were removed. These findings highlighted the resilience of salmon populations and the broader benefits of restoring natural river flows, including improved water quality, sediment transport, and habitat connectivity. Tribal leaders also played a pivotal role in shaping the narrative around the dam removal project, emphasizing the interconnectedness of ecological health and cultural survival. Their voices brought a moral urgency to the issue, reminding stakeholders that the Klamath River was not just a resource to be managed but a living entity deserving of respect and care. This perspective resonated deeply with many, helping to build the broad coalition needed to move the project forward. By the time the dams were finally removed in 2024, the effort had become a symbol of what can be achieved through collaboration and perseverance. For the tribes, it was a moment of profound vindication, a testament to the power of their advocacy and the strength of their cultural connection to the river. The sight of salmon returning to their ancestral waters less than a month after the dams came down was a victory not just for the fish but for the people who had fought so hard to bring them home. Part 4: Broader Implications for Environmental Justice and Indigenous Sovereignty The successful removal of the Klamath River dams and the subsequent return of salmon to their ancestral spawning grounds represents more than an environmental achievement. It is a triumph for Indigenous sovereignty and a landmark in the global fight for environmental justice. This project highlights the power of centering Indigenous voices in conservation efforts and serves as a model for addressing historical injustices while fostering collaboration between diverse stakeholders. For the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes, the restoration of the Klamath River is inseparable from their broader struggle for self-determination and cultural survival. The fight to remove the dams was not just about restoring salmon populations but about reclaiming their rightful role as stewards of the land and water. The river, in their worldview, is a living entity with intrinsic value, and its health is directly tied to the well-being of their communities. By advocating for the river’s restoration, the tribes were also asserting their sovereignty, challenging a legacy of margi

mostra meno